Inspiration

Before the Nobel, There Was a Teacher

Before Albert Camus was the voice of a generation, he was an invisible child in a house without books. He was a boy whose future was already written by the harsh ink of illiteracy and loss. Then came the intervention that changed everything. Decades later, at the pinnacle of human achievement, Camus would look back at his Nobel Prize and realize it was built upon a foundation laid by a single elementary school teacher. “I remain your grateful pupil,” Camus wrote to his mentor—a phrase that serves as a timeless anthem for every educator who has ever looked at a struggling student and said: You matter.

The Day Everything Changed

Paris, October 1957

Albert Camus was 43 years old when the telegram arrived.

He unfolded the message and read the words that would secure his place in literary history: he had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

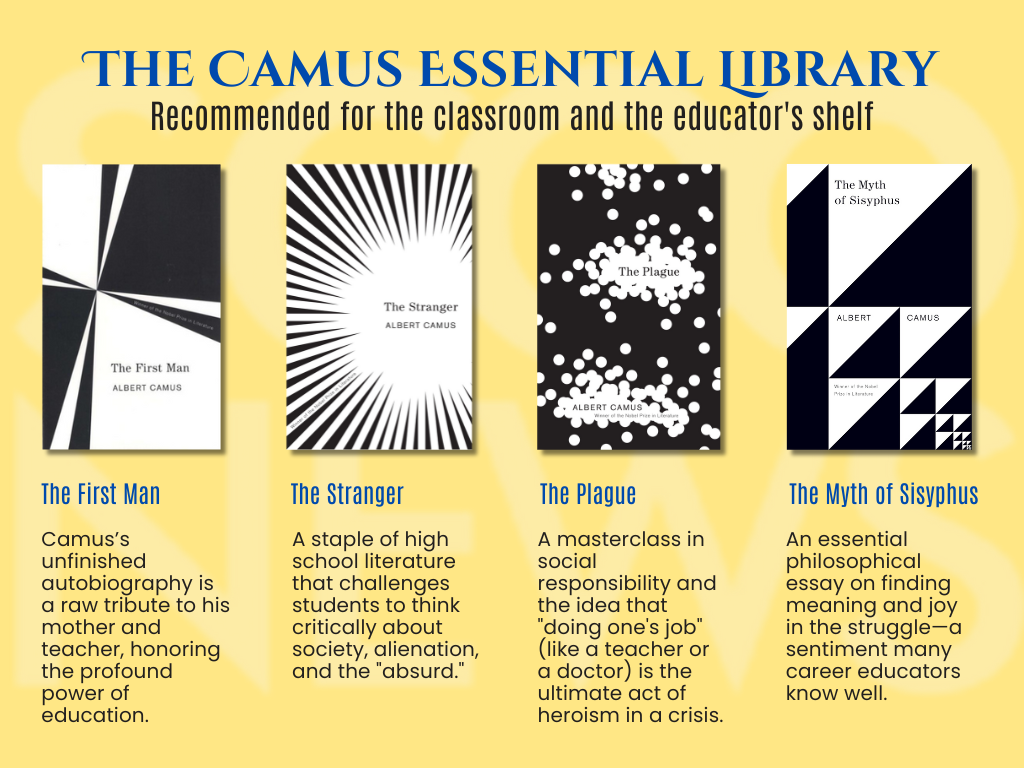

He was one of the youngest recipients ever. The world saw him as the conscience of his generation — the author of The Stranger, The Plague, The Myth of Sisyphus — a writer who had captured the absurdity and alienation of modern life.

The celebrations would soon follow: journalists, interviews, speeches, congratulations.

But Camus’ mind went somewhere else entirely.

After thinking of his mother, he thought of a man in a quiet classroom many years earlier — the teacher who had once looked at a poor, silent boy and seen a future no one else imagined.

That night, Camus sat down to write a letter.

A Childhood on the Margin

Born Into Poverty — French Algeria, 1913

To understand the letter, you must understand where Camus began.

Albert Camus was born in Mondovi, French Algeria, on November 7, 1913.

His father, Lucien, was killed in World War I before Albert turned one. His mother, Catherine, was partially deaf, nearly illiterate, and worked as a cleaner so her children could eat.

The family lived in a cramped apartment in the working-class Belcourt district of Algiers — no electricity, no running water, no books. Poverty wasn’t merely a condition; it was an entire world with sharply defined limits.

In such neighborhoods, school was a holding place. Working-class children learned the basics, then quit to earn wages. No one expected one of them to become a writer.

Camus sat in class: thin, watchful, quiet. A child easy to overlook.

Except one person didn’t overlook him.

The Teacher Who Refused to Let Him Disappear

Louis Germain’s Quiet Intervention

Louis Germain, Camus’ elementary school teacher, noticed something unusual about the boy:

- the intensity in his eyes

- the way he listened

- the unresolved questions beneath his silence

Germain decided that poverty would not define this child’s future.

He gave Albert extra help.

He handed him books — more than the boy had ever seen at home.

He stayed after school to explain ideas, encourage curiosity, and open windows Camus never knew existed.

Then came the decisive moment: the competitive exam for admission to lycée, the gateway to higher education — a path almost never offered to children of Camus’ background.

Germain tutored him personally.

He convinced administrators to let Albert sit for the exam.

He prepared him, defended him, believed in him.

Camus passed.

From that moment, his life opened: secondary school, university, journalism, Resistance work during World War II, philosophy, novels, essays — and eventually, worldwide recognition.

But beneath every achievement was that first act of belief.

Camus never forgot it.

The Letter of Gratitude

November 19, 1957

After the Nobel Prize announcement, Camus waited for the noise to fade.

Then he wrote to “Monsieur Germain.”

He thanked his teacher for the kindness and patience shown to a poor child who needed someone to see him. He confessed that when the Nobel news arrived, after his mother, his first thought was of Germain.

He wrote that without his teacher’s influence, none of his success would have existed. He wanted Germain to know that the time, the generosity, and the belief he had invested in that quiet boy lived on in the man the world now celebrated.

Camus ended with a line that has echoed through generations:

“I remain your grateful pupil.”

The Teacher’s Reply

A Humble Answer From Across the Years

Louis Germain, now an older man, wrote back.

He did not take credit for shaping a great writer.

Instead, he expressed the simple joy of having helped a student use his education well — that, he said, was the true reward of teaching.

Across decades and continents, they met again — not in a classroom, but in a pair of letters that captured the enduring connection between a teacher and a child who needed one.

The Final Pages of a Short Life

January 4, 1960 — The Last Journey

Just over two years after receiving the Nobel Prize, Camus died in a car accident on January 4, 1960. He was 46.

In his briefcase, investigators found the unfinished manuscript of The First Man, a novel in which he began exploring his childhood and the two figures who shaped him most deeply: his mother and his teacher.

Among his belongings were the letters from Louis Germain — carefully preserved, carried with him always.

Even at the height of fame, he kept tangible proof of who opened the door for him.

The Quiet Heroes Behind Every Success

The Camus–Germain Story Is Not Just Theirs

This isn’t only a story about Albert Camus and one extraordinary teacher.

It’s about the invisible army of Louis Germains everywhere:

- the teacher who gave you books because you were hungry for more

- the professor who took your questions seriously

- the mentor who wrote a recommendation letter that changed your life

- the adult who said: You matter. Keep going.

Most will never receive thank-you letters from Nobel laureates.

Many will retire never knowing which seeds they planted grew into forests.

Yet somewhere, a child they believed in is building a life once thought impossible.

What Camus Teaches Us

Success Is Never Self-Made

Camus’ letter cuts through the myth of self-made genius:

Look back.

Remember who saw you when you were invisible.

Say thank you while you can.

Albert Camus won the Nobel Prize at 43.

His first instinct wasn’t I earned this.

It was I owe this.

In a universe he believed lacked inherent meaning, Camus chose gratitude — a meaning built from memory, humility, and human connection.

He remembered the woman who cleaned houses so he could attend school.

He remembered the teacher who stayed late to explain how the world worked.

He remembered the moment someone reached across poverty and said:

You matter. You can go further.

And he said thank you.