Inspiration

Here’s toasting the awardees for the year 2019… Shine on, Jewels of India!

ScooNews celebrated the work and tireless spirit of the Jewels of India for the year 2019 at the third edition of the ScooNews Global Educators Fest 2019 at Udaipur.

It is no secret that education has the potential to write and rewrite the destiny of generations. This responsibility is shouldered by no one in particular and simultaneously by all working in the field of education. Amidst the thousands of educators, a few shine brighter and become a beacon of inspiration, a benchmark that other educators strive to equal. 'Jewels of India' is a humble initiative by ScooNews to honour such extraordinary educators.

A truly unique initiative, the awardees are not selected on the basis of nominations. In-depth, year-round research has focused on identifying educators who are making a far-reaching impact in the field of education and have the potential to inspire fellow educators to change the game.

In our eyes and through the eyes of respected names from the field of education, these are the educators who have chosen not only to set new standards but have also blazed a path for others.

ScooNews felicitated the work and tireless spirit of the Jewels of India for the year 2019 at the third edition of the ScooNews Global Educators Fest 2019 at Udaipur.

Here’s toasting the awardees for the year 2019… Shine on, Jewels of India!

When experience meets excellence…

Rama Datt

A committed and disciplined educationalist, Rama Datt is executive trustee, Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum Trust, Jaigarh Public Charitable Trust, and Trustee, Shila Devi Temple Trust. She did her schooling and college in science stream in Dehradun. The inspiration came from her mother who was a strong and hardworking educationalist.

Datt has excelled in the field for more than 37 years and continues to make education easy, enjoyable and multidimensional at all levels. Her innovative policies have been accepted and appreciated by the entire nation. She has worked at Sawai Man Singh Vidyalaya, Jaipur from 1984 to 1996. She has held the position of founder principal of Mahaveer Public School, Jaipur from 1996 to 2003 successfully, where she introduced the lottery system. Datt has also steered Sanskar School, Jaipur from 2004 to 2017 and is an advisor to the same institution.

She is a member of the governing body of Maharaja Sawai Bhawani Singh School and The Palace School. Sticking true to her beliefs, she is also associated with Disha where she conducts teacher training programs. A worthy educator, resource-person and scholar, she has had various articles published in newspapers on parent-teacher relations, their role in the development of children, the concept of education and many such topics. Her emphasis on the student resource centre and teacher resource centre has brought a holistic change in the teaching process, especially in schools she has guided under her leadership.

Globally, Datt has been invited for exchange programmes to Germany, USA and UK for her outstanding contribution in the field of education while her work has been felicitated by various organisations. In 2002, she was honoured by the society of unaided private schools of Rajasthan along with Shri Radhakrishnan Samman by Avantika. Amidst the many awards that were bestowed upon her, she received Sawai Pratap Singh Award in 2005, Best Educationist Award in 2012, Certificate of Excellence by the International Institute of Management & Education and National Mahila Gold Medal by Indian Solidarity Council, to name a few.

Under her leadership, Sanskar School received an award for being one of the best schools in India; it also became the first Microsoft school.

Datt’s philosophy in life is to work on something that outlasts life itself.

ScooNews salutes the feisty spirit of Rama Datt, a jewel of India indeed!

Bringing back the joy of childhood

Lina Ashar

Lina Ashar is the founder of Kangaroo Kids & Billabong High. Lina started her career as a teacher and today is one of the most renowned educators and edupreneurs in India. Lina did her primary schooling from England before moving to Australia, where she acquired a Bachelor’s degree in Education from Victoria College, Melbourne.

In 1991, she came to India on a year-long sabbatical from college. While connecting with her roots, she ended up taking a teaching stint at a prestigious heritage school in suburban Mumbai, an experience that changed her life and led to the burning question “How can she bring back the joy of childhood for the children in India?”

Back then, the education system in India was still grappling with a straitjacketed approach to education. It was robbing children of their childhood.

The conviction to offer an education that set the child at the centre, began with a preschool in Bandra (Mumbai) in the year 1993 with 25 students. With a successful formula at hand, she went from one preschool (Kangaroo Kids) to a network of them, whilst branching out to high schools (Billabong High International School) as well. The journey of developing child-centric schools across 44+ different cities in India and across Dubai, Maldives and Qatar has been an outstanding one, supported by parents, education partners and a fierce team of dedicated, passionate and determined individuals at the school and central team level.

In her endeavour to make a difference in every child’s life, she wrote her first book called ‘Who Do You Think You Are Kidding’. The book dealt with parenting for children and is a complete guide for parents on how to build a positive child right from the start. Her second book ‘Drama Teen’, is a guide for both parents and teens.

The industry has recognised and awarded her efforts several times over for her unique and meaningful contributions to the sector, notable among them being the A.P.J Abdul Kalam Award for ‘Excellence in Education’ at the 46th National Summit on Start-Ups and Women Entrepreneurship and the Award for 'Exemplary Contribution in ECCE of the year working for young children and their education' by ECA Awards held at the Early Ed Asia Conference – Jaipur 2019.

A journey of commitment & change

Lt. Gen. Surendra Kulkarni

Known for his wit and honest thoughts on the changes required in the Indian education system, Lt Gen Surendra Kulkarni is an Old Boy of Mayo College. He joined in 1964 and completed his MSc in March 1970. He has served in the Army for nearly four decades. He was commissioned into the Armoured Corps in 1975. In his long and distinguished career, he has commanded the largest forces and held some of the most prestigious assignments. In recognition of his special contribution, he has been awarded a Vishisht Seva Medal twice, an Ati Vishishta Seva Medal and finally the highest peacetime distinguished service award in the Armed Forces, the Param Vishisht Seva Medal by the President of India.

Parallel to his Army career, he has pursued his academic interests. He is an Economics graduate from Fergusson College Pune. He was a post-graduate UGC Merit scholar before he joined the Army. He has four Master’s Degrees including an M Phil degree. He would be one of the few officers to have been sent abroad thrice on academic assignments. He has taught at the Armoured Corps Centre and School, Ahmadnagar, Institute of Armament Technology, Pune and the Defence Services Staff College, Wellington. In Mayo, he was in Colvin and Rajasthan Houses. He was a keen sportsman, who played cricket, tennis, squash, football, and hockey.

He was also a part of the FICCI Arise Indian delegation that went to attend the Learning Conference in London in January 2019. He has spoken at various panel discussions such as the Mad Conclave and ScooNews Global Educators Fest 2018, to name a few and has provided some key insights using years of his experience.

He is known for blending the traditional approaches with modern practices, fostering knowledge through innovation and engagement and equipping the students with the best work habits, character traits, and 21st-century skills. Under his leadership, Mayo College got recognised as a “Great Place to Study” based on Student Satisfaction Index and received the National School Excellence Award for outstanding commitment and exceptional efforts in promoting co-curricular education. They are India’s Best Boarding School branded by International Brand Consulting Corporation, USA. Some other awards include “Top 10 Boys Boarding School in India”, “Top 50 Schools in India” and “Most Trusted Brand in Education”, “Asia’s Best Private Education Institute”, India’s Most Respected School”, “Most Trusted Brand in Education” and “Green Schools Award”.

Pioneer of early childhood education

Venita Kaul

Prof Kaul is currently Professor Emerita (Education) and Executive Chair of Advisory Committee for the Centre for Early Childhood Education and Development (CECED), Ambedkar University Delhi, since January 2017. She Joined Ambedkar University Delhi in 2009 as Professor and Founder Director of Centre for Early Childhood Education and Development (CECED) and later took over additional responsibility as Dean/Director of the School of Education Studies. She retired from these positions in December 2016.

Prior to 2009, Prof Kaul was a Senior Education Specialist in the World Bank for about 10 years, wherein she led several World Bank projects in India Elementary Education and Early Childhood Education (ECE), including World bank’s support to Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, ICDS, and District Primary Education Programme (DPEP). She was also involved in projects in other countries in the South Asian region viz, Maldives, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal. Preceding her tenure in the World Bank, Prof Kaul spent over 20 years at NCERT from 1975 to 1998, from where she took voluntary retirement as Professor and Head, Department of Preschool and Elementary Education. For two years she served as a headmistress of the IIT Nursery school, which was a collaborative initiative between NCERT and IIT, Delhi. She has a number of publications to her credit.

In the Ambedkar University Delhi, she established the Centre for Early Childhood Education and Development (CECED), primarily as a centre for policy research and advocacy, which is the first of its kind at the university level in India, and which has now been recognised as a national resource institution in ECCE. She led the establishment of a Master’s programme in Early Childhood Care and Education, initially as a pilot, which has now been regularised and continues to draw a large number of students. She led a major longitudinal, mixed-method research titled India Early Childhood Education Impact Study (IECEI) in three states of India, the first of its kind. It provided valuable policy level insights and findings which have informed the recommendations of the Draft National Policy on Education (2019) which has duly acknowledged this source.

She received the award of Exemplary Contribution in ECCE of the Year for Working for Young Children and their Education in 2016 by the Early Childhood Association, India and she was as Felicitated for Lifetime Contribution to Early Childhood Development by Association for Early Childhood Education and Development (AECED), Mumbai in 2018.

Dr. Swati Popat Vats received the Jewels of India Award on behalf of Dr. Venita Kaul.

Inspiring educationists worldwide

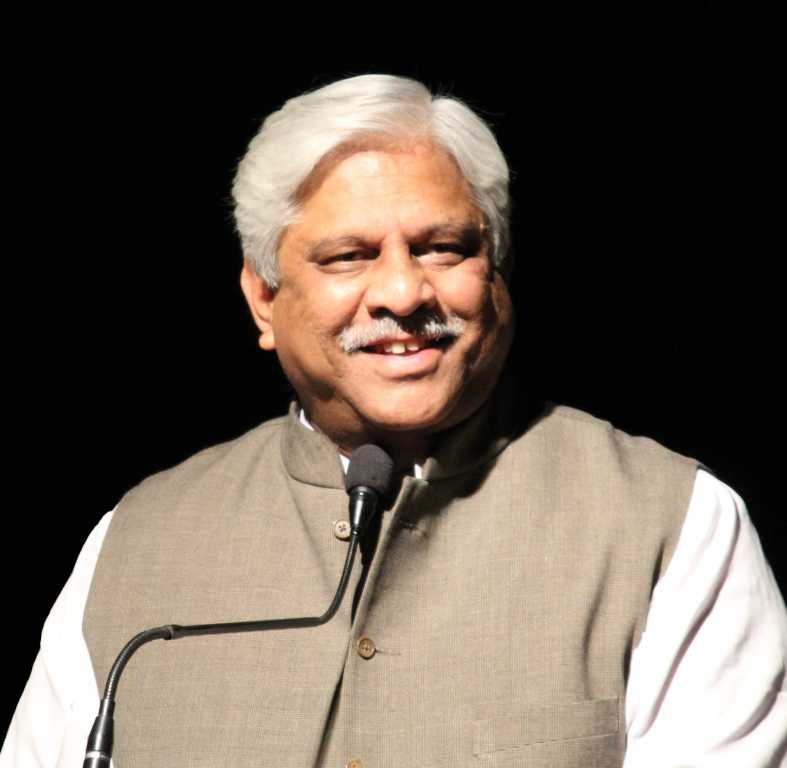

Pramod Sharma

Pramod Sharma brings with him the experience of a career in education spanning 46 years. He started with teaching chemistry in 1972 at the Doon School, Dehradun. He also taught in India School, Kabul, Afghanistan from 1976 to 1979, then Ijebu Ode Grammar School, Nigeria from 1981 to 1985. He has served as a Principal for over 29 years across various institutions, including the TN Academy, Gangtok, Yadavindra Public School, Patiala, Mayo College, Ajmer and Genesis Global School, Noida. During his 13-year tenure at Mayo College, Ajmer, it was ranked repeatedly amongst the best two residential schools in India.

He was additional head examiner, CBSE, New Delhi Examiner ‘O’ level, West African Exams Council, Nigeria. He visited and stayed at Eton College, Loretto School, Edinburgh, Cheltenham college, Oakham School in the UK and Deerfield Academy, New England USA to study their teaching methods and resource utilisation in the summer of 1988 and again in 2000.

He was awarded the National Award for Teachers in 2000 by the President of India. His decade-long tenure as a member of the Governing Body of the CBSE was much commended. He is the ex-Chairman of the Indian Public Schools Conference (IPSC) and the recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award from IPSC in 2008. He is an Honorary Member of Round Square and IPSC. As a Founder Principal, Director and now Vice-President of the Managing Committee of Genesis Global School, Noida, he feels very satisfied looking at the growth of GGS in such a short span of time. He has been Convenor INTACH, Ajmer and Pushkar, and Vice-Chairman of the Rajasthan Scouts and Guides. He is an honorary member of Round Square and IPSC. An avid sportsperson, he continues to enjoy tennis and badminton.

Most recently, he has been conferred with the Lifetime Achievement in Education Leadership Award 2018 by Education World.

Inspiration

Before the Nobel, There Was a Teacher

Before Albert Camus was the voice of a generation, he was an invisible child in a house without books. He was a boy whose future was already written by the harsh ink of illiteracy and loss. Then came the intervention that changed everything. Decades later, at the pinnacle of human achievement, Camus would look back at his Nobel Prize and realize it was built upon a foundation laid by a single elementary school teacher. “I remain your grateful pupil,” Camus wrote to his mentor—a phrase that serves as a timeless anthem for every educator who has ever looked at a struggling student and said: You matter.

The Day Everything Changed

Paris, October 1957

Albert Camus was 43 years old when the telegram arrived.

He unfolded the message and read the words that would secure his place in literary history: he had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

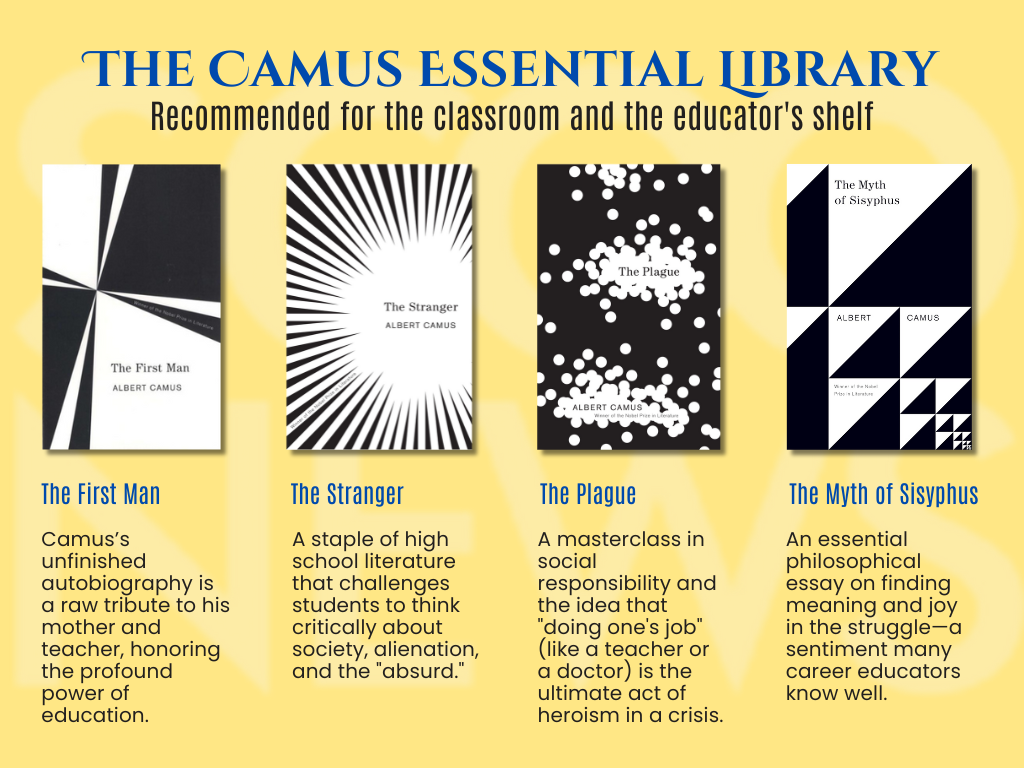

He was one of the youngest recipients ever. The world saw him as the conscience of his generation — the author of The Stranger, The Plague, The Myth of Sisyphus — a writer who had captured the absurdity and alienation of modern life.

The celebrations would soon follow: journalists, interviews, speeches, congratulations.

But Camus’ mind went somewhere else entirely.

After thinking of his mother, he thought of a man in a quiet classroom many years earlier — the teacher who had once looked at a poor, silent boy and seen a future no one else imagined.

That night, Camus sat down to write a letter.

A Childhood on the Margin

Born Into Poverty — French Algeria, 1913

To understand the letter, you must understand where Camus began.

Albert Camus was born in Mondovi, French Algeria, on November 7, 1913.

His father, Lucien, was killed in World War I before Albert turned one. His mother, Catherine, was partially deaf, nearly illiterate, and worked as a cleaner so her children could eat.

The family lived in a cramped apartment in the working-class Belcourt district of Algiers — no electricity, no running water, no books. Poverty wasn’t merely a condition; it was an entire world with sharply defined limits.

In such neighborhoods, school was a holding place. Working-class children learned the basics, then quit to earn wages. No one expected one of them to become a writer.

Camus sat in class: thin, watchful, quiet. A child easy to overlook.

Except one person didn’t overlook him.

The Teacher Who Refused to Let Him Disappear

Louis Germain’s Quiet Intervention

Louis Germain, Camus’ elementary school teacher, noticed something unusual about the boy:

- the intensity in his eyes

- the way he listened

- the unresolved questions beneath his silence

Germain decided that poverty would not define this child’s future.

He gave Albert extra help.

He handed him books — more than the boy had ever seen at home.

He stayed after school to explain ideas, encourage curiosity, and open windows Camus never knew existed.

Then came the decisive moment: the competitive exam for admission to lycée, the gateway to higher education — a path almost never offered to children of Camus’ background.

Germain tutored him personally.

He convinced administrators to let Albert sit for the exam.

He prepared him, defended him, believed in him.

Camus passed.

From that moment, his life opened: secondary school, university, journalism, Resistance work during World War II, philosophy, novels, essays — and eventually, worldwide recognition.

But beneath every achievement was that first act of belief.

Camus never forgot it.

The Letter of Gratitude

November 19, 1957

After the Nobel Prize announcement, Camus waited for the noise to fade.

Then he wrote to “Monsieur Germain.”

He thanked his teacher for the kindness and patience shown to a poor child who needed someone to see him. He confessed that when the Nobel news arrived, after his mother, his first thought was of Germain.

He wrote that without his teacher’s influence, none of his success would have existed. He wanted Germain to know that the time, the generosity, and the belief he had invested in that quiet boy lived on in the man the world now celebrated.

Camus ended with a line that has echoed through generations:

“I remain your grateful pupil.”

The Teacher’s Reply

A Humble Answer From Across the Years

Louis Germain, now an older man, wrote back.

He did not take credit for shaping a great writer.

Instead, he expressed the simple joy of having helped a student use his education well — that, he said, was the true reward of teaching.

Across decades and continents, they met again — not in a classroom, but in a pair of letters that captured the enduring connection between a teacher and a child who needed one.

The Final Pages of a Short Life

January 4, 1960 — The Last Journey

Just over two years after receiving the Nobel Prize, Camus died in a car accident on January 4, 1960. He was 46.

In his briefcase, investigators found the unfinished manuscript of The First Man, a novel in which he began exploring his childhood and the two figures who shaped him most deeply: his mother and his teacher.

Among his belongings were the letters from Louis Germain — carefully preserved, carried with him always.

Even at the height of fame, he kept tangible proof of who opened the door for him.

The Quiet Heroes Behind Every Success

The Camus–Germain Story Is Not Just Theirs

This isn’t only a story about Albert Camus and one extraordinary teacher.

It’s about the invisible army of Louis Germains everywhere:

- the teacher who gave you books because you were hungry for more

- the professor who took your questions seriously

- the mentor who wrote a recommendation letter that changed your life

- the adult who said: You matter. Keep going.

Most will never receive thank-you letters from Nobel laureates.

Many will retire never knowing which seeds they planted grew into forests.

Yet somewhere, a child they believed in is building a life once thought impossible.

What Camus Teaches Us

Success Is Never Self-Made

Camus’ letter cuts through the myth of self-made genius:

Look back.

Remember who saw you when you were invisible.

Say thank you while you can.

Albert Camus won the Nobel Prize at 43.

His first instinct wasn’t I earned this.

It was I owe this.

In a universe he believed lacked inherent meaning, Camus chose gratitude — a meaning built from memory, humility, and human connection.

He remembered the woman who cleaned houses so he could attend school.

He remembered the teacher who stayed late to explain how the world worked.

He remembered the moment someone reached across poverty and said:

You matter. You can go further.

And he said thank you.

Inspiration

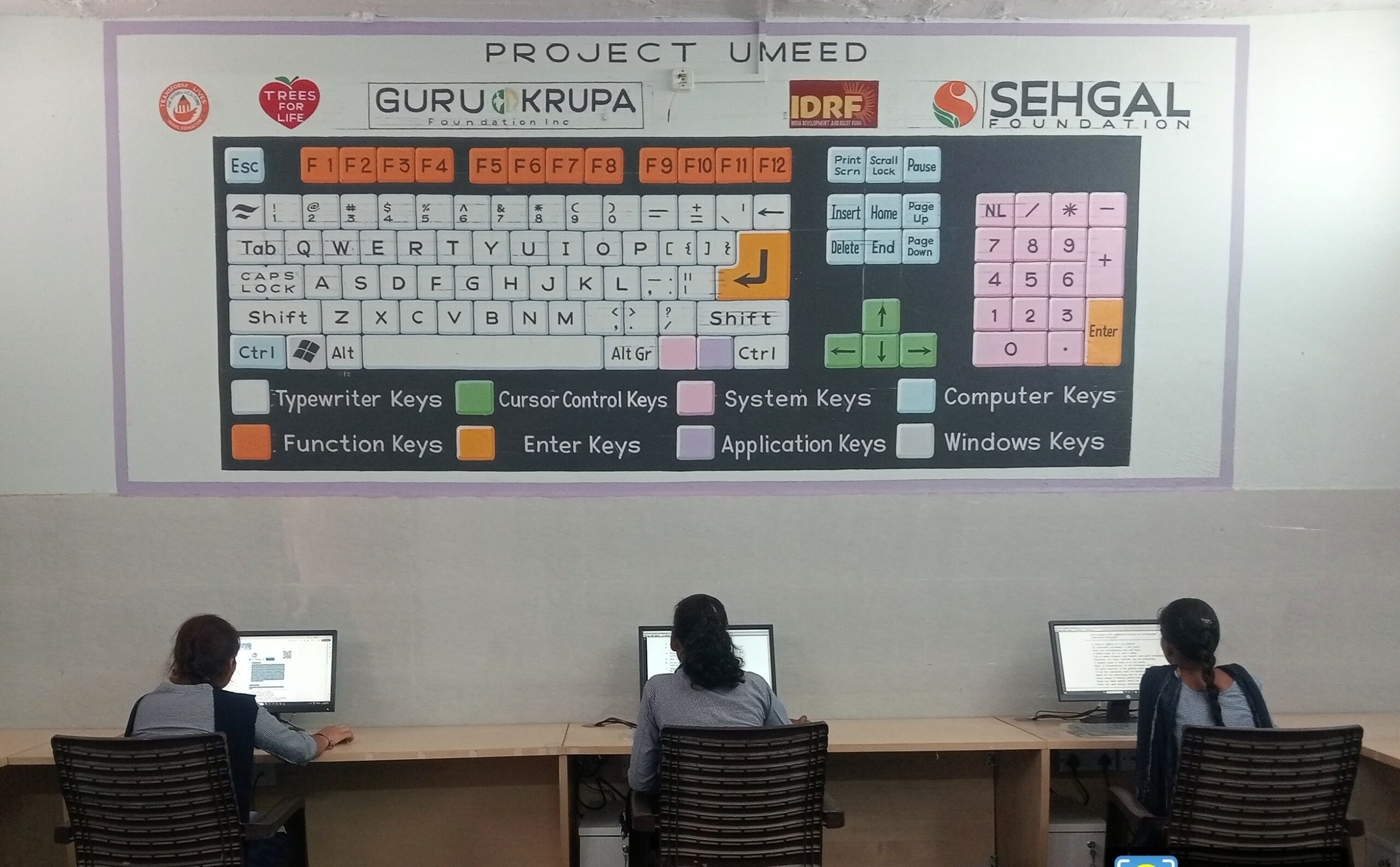

Umeed: A Ray of Hope for Better Tomorrow

“I used to be hesitant to speak on stage, but after participating in the life skills sessions, I gained confidence. Thanks to Project Umeed,” shared Sanjana, student of Government Senior Secondary School, Kurthala, Nuh, Haryana.

The project Umeed creates equitable learning opportunities for rural schoolchildren by providing enhanced Digital and Life Skills Awareness (DLSA), leading to their overall learning and empowerment. The project is a partnership with Teach for Life supported by Trees for Life, India Development, and S M Sehgal Foundation, which is implementing the project on the ground.

The DLSA course has been operational at Government Senior Secondary School, located in village Kurthala, block Nuh, Haryana, since March 2025. Sixty students are enrolled in this course that is led and facilitated by a dedicated instructor.

The course covers essential topics related to learning about computers, technology, and cyber safety; developing important social and emotional abilities in children; building self–confidence, providing career guidance for goal setting; gaining knowledge about local participation for village development, familiarity with key government programs, and becoming informed, engaged citizens.

Topics such as “Me and My Self” and “Communication Skills” boost children’s confidence strengthen their thinking abilities and communication aptitudes.

Students Shine at the Youth Parliament

With this new learning and enthusiasm, two girl’s students, Sanjana and Renu from Govt. Sr. Sec. School, Kurthala, Nuh, who attend the DLSA classes, were selected for the Youth Parliament program. They were both excited and a little hesitant. They diligently prepared and practiced their skills on effective communication, brainstorming and role playing for over a month. Finally, on the day of the event, the entire auditorium erupted in applause as the girls confidently shared their thoughts on the Youth Parliament. Sanjana moderated the event as speaker, and Renu presented her views as finance minister. Other students participated as members of Parliament. The whole process further strengthened the students’ understanding of social issues and the democratic process. The event showcased the students’ development of confidence and leadership skills.

“I realized how important it is to present your thoughts clearly. This experience helped me hone my life skills, especially the topics of communication skills and ‘Me and Myself’ had a deep impact on me.” – Renu, student, Govt. Sr. Sec. School, Kurthala, Nuh, Haryana

The same course is being conducted at Government Senior Secondary School, Badarpur village, bock Nagina, district Nuh, with another sixty students. As part of their digital awareness sessions, students learned how to use computers and online platforms to access government programs and services. They were taught the importance of the Aadhaar card and guided through the process of downloading or updating their Aadhaar credentials. Students were made aware that their Aadhaar card serves to establish and safeguard their identity, enabling them to access government services and avail different benefits.

Earlier, the students had to depend on the Common Service Centre or Aadhaar Seva Kendras, located 2–3 km away from the village, to download or update government documents such as the Aadhaar card, ration card, or other certificates. Each time they had to update their documents, they had to pay a fee of as much as Rs 100, plus a transportation cost of Rs20. Even then, issues often remained unresolved, forcing them to make repeated trips.

With their newfound confidence in using technology, students no longer need to visit CSC centres and Aadhaar service centres repeatedly, thus saving both time and money. This experience has proven to be a significant step toward achieving autonomy.

The students’ parents and the village council were deeply impressed by this initiative. They expressed their gratitude to S M Sehgal Foundation and urged that more such digital awareness courses should run in the future, so that other people of the village can also become digitally empowered.

About the Authors: Indu Verma, Sr. Program Lead, Transform Lives one school at a time, S M Sehgal Foundation

Mahesh Sharan and Mosim Khan, Instructors, Transform Lives one school at a time, S M Sehgal Foundation

Education

17-year-old Innovator Designs Learning Tools for the Visually Impaired

At just 17, Singapore-based student Ameya Meattle is proving that age is no barrier to impact. What began as a small idea to make education more accessible has evolved into a mission that is transforming how visually impaired learners experience learning and skill development.

Ameya founded Earth First at the age of 14 — a social enterprise that helps visually impaired individuals “earn and learn” by creating sustainable, eco-friendly products. Working with eight NGOs across India and Singapore, the initiative has trained more than 100 visually impaired students and launched over 23 sustainable product lines, from tote bags and jute placemats to macramé planters. Each design is adapted to provide hands-on learning opportunities and help trainees gain confidence in both craft and enterprise.

Beyond social entrepreneurship, Ameya has focused deeply on education and technology. He led a Python programming course for 50 visually impaired students, designing custom training modules that made coding accessible through screen readers and tactile tools. By introducing technology as a viable career pathway, Ameya hopes to help students move from manual tasks to high-skill, digital opportunities.

His work also extends into assistive technology research. Under the mentorship of Dr. Pawan Sinha at MIT, Ameya developed a VR-based diagnostic game to assess visual acuity in children — turning the process into an interactive experience rather than a clinical test. The tool is being piloted at MIT’s Sinha Lab and with Project Prakash in India, helping doctors evaluate and track visual development before and after eye surgeries.

In addition, during his internship at the Assistech Lab at IIT Delhi, Ameya worked on designing tactile STEM teaching aids, such as accessible periodic tables and coding tutorials for visually impaired learners. His goal, he says, is not just to innovate but to make scientific learning inclusive and joyful for all.

Ameya’s work highlights how education, empathy, and innovation can intersect to create a more equitable future — one where technology serves not just progress, but people.

Education

Class 11 Student Navya Mrig on a Mission to Bust Myths About Organ Donation

Saahas, a Delhi-based non-profit organisation founded by Class 11 student Navya Mrig of The Ram School, Moulsari, Gurugram, is creating awareness about organ donation and working to counter myths that prevent families from giving timely consent.

Established in 2024, Saahas focuses on every aspect of organ donation, particularly deceased organ donation where family approval must be granted quickly. The organisation highlights that hesitation and misinformation often stop families from making decisions that could save lives.

To address this, Saahas conducts workshops, myth-busting talks, and seminars in schools, resident welfare associations, hospitals, and workplaces. These sessions explain processes such as brain-stem death certification and the role of family consent in simple, clear terms. Each session concludes with practical guidance, ensuring participants leave with both knowledge and actionable steps.

The initiative has also developed resource kits with slide decks, facilitator notes, QR-linked checklists, and referral contacts to make it easier for schools and institutions to host repeatable sessions. Saahas partners with community groups and healthcare institutions to co-host Q&A sessions with clinicians and transplant coordinators, and also honours donor and recipient families through small ceremonies that highlight the impact of organ donation.

At its core, Saahas is designed to bring organ donation discussions into everyday spaces rather than waiting for the urgency of hospital decisions. By focusing on conversations in classrooms, community meetings, and staff rooms, the organisation aims to gradually build a culture where organ donation is better understood and more widely accepted.

Navya’s initiative reflects how young people are increasingly taking up important social causes and contributing to public awareness campaigns with structured, replicable models.

(News Source- ANI)

Education

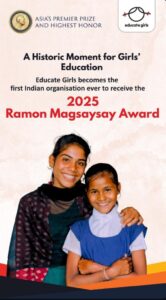

Educate Girls Becomes First Indian NGO to Win the Ramon Magsaysay Award

In a landmark recognition for Indian education and grassroots activism, Educate Girls, founded by Safeena Husain, has been named one of the recipients of the 2025 Ramon Magsaysay Award. Often referred to as Asia’s Nobel Prize, this honour highlights the organisation’s transformative work in enrolling and empowering out-of-school girls across some of India’s most remote and underserved regions.

The announcement marks a historic moment — Educate Girls is the first Indian organisation to ever receive this award, underscoring the global importance of its mission. Alongside Educate Girls, the other awardees include Shaahina Ali from the Maldives for her environmental work and Flaviano Antonio L. Villanueva from the Philippines. The formal ceremony will take place on November 7 at the Metropolitan Theatre in Manila.

Safeena Husain: From Teacher Warrior to Global Recognition

For ScooNews, this moment carries a special resonance. In 2018, Safeena Husain was celebrated as a Teacher Warrior, honoured for her vision of tackling gender inequality at the root by ensuring that every girl receives access to education. What started as a 50-school test project in Rajasthan has since scaled into an expansive movement spanning 21,000 schools across 15 districts, supported by a network of 11,000+ community volunteers known as Team Balika.

Her journey, as she has often recalled, was shaped by both personal and professional turning points. After studying at the London School of Economics and working in grassroots projects across Latin America, Africa, and Asia, Safeena returned to India, deeply aware of the entrenched discrimination girls faced. A family encounter in a village, where her father was pitied for not having a son, crystallised her resolve to fight for gender equity through education.

Breaking Barriers in Education

Educate Girls has gone beyond enrolling girls into schools. Its programmes aim at:

-

Increasing enrolment and retention of out-of-school girls

-

Improving learning outcomes for all children in rural districts

-

Shifting community mindsets through participation and ownership

The organisation has also pioneered innovative financing models such as the world’s first Development Impact Bond (DIB) in education, tying funding directly to learning outcomes.

Safeena has often spoken about the transformative power of education citing stories of girls who once had no aspirations simply because nobody asked them what they wanted to be, and who today, thanks to education, dream of becoming doctors, teachers, or even police officers.

Global Platforms, Indian Roots

Safeena’s vision has found resonance globally. In her TED Talk titled “A Bold Plan to Empower 1.6 Million Out-of-School Girls in India”, she emphasised that girls’ education is the closest thing we have to a silver bullet for solving some of the world’s toughest problems from poverty to health to gender inequality. In 2023, she was also awarded the WISE Prize for Education, cementing her reputation as one of the leading voices in education worldwide.

But even as Educate Girls receives international acclaim, its deepest impact continues to be felt in the dusty lanes of rural Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, where every single enrolment represents a victory against entrenched social barriers.

Why This Award Matters

The Ramon Magsaysay Award not only recognises Safeena Husain’s leadership but also places Indian NGOs on the global stage. It sends a powerful message: education is both the foundation of equity and the key to transformation. For India, a country with one of the world’s largest populations of out-of-school girls, this award validates years of struggle, innovation, and community-driven action.

For ScooNews, which first honoured Safeena as a Teacher Warrior in 2018, this moment is both proud and historic. It shows that when educators and changemakers stay rooted in their vision, their work can resonate far beyond borders.

Education

In Every Smile, a Victory – Sandhya Ukkalkar’s Journey with Jai Vakeel’s Autism Centre

For Sandhya Ukkalkar, the path to becoming an educator in the field of special education was never just a professional decision — it was deeply personal. It began in the quiet, determined moments of motherhood, as she searched for a school that could truly understand her son’s unique needs. Diagnosed with Autism and Intellectual Disability, he required more than care — he needed acceptance, structure, and a nurturing environment.

In 1996, a compassionate doctor guided her to Jai Vakeel School. From the moment her son was enrolled, Sandhya witnessed a transformation that brought not only relief, but hope. Encouraged by the school’s doctor, she enrolled in a special education course, and by June 2000, she returned to the same institution — this time as a teacher. Over the years, she grew into the role of Principal of the Autism Centre at Jai Vakeel, dedicating her life to children who, like her son, simply needed to be seen, understood, and supported.

What sets the Autism Centre apart is not just its experience or legacy, but its guiding philosophy: a child-led, strengths-based approach that celebrates neurodiversity. Here, each learner follows an Individualised Education Plan (IEP), supported through small groups, one-on-one sessions, and methodologies that include Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA), Sensory Integration, and Visual Supports. The goal isn’t to fit children into a mould but to honour their unique ways of engaging with the world.

Serving children aged 3 to 18, the centre focuses on early intervention, functional academics, and pre-vocational training — all grounded in a multisensory curriculum aligned with NCF and NCERT. For the 31 students with Autism and Intellectual Disability who currently attend, the emphasis lies on building communication and sensory skills that can translate into real-world independence.

Sandhya believes collaboration is the cornerstone of success. At the centre, therapists, educators, parents, and healthcare professionals work as a unified team. Over 75% of the children served come from low-income families, and many receive free or subsidised education and therapy through rural camps and outreach programs.

“These aren’t luxuries,” Sandhya insists, referring to tools like sensory rooms and assistive tech. “They’re essentials.”

And the results are deeply moving. Children who once struggled with attention now engage joyfully in sessions. Some who were non-verbal begin to use gestures, visuals, and eventually words. Others transition into mainstream schools. One student, now preparing for CA exams, once needed foundational classroom readiness support. These are not isolated cases — they are the product of consistent, individualised attention and belief.

For Sandhya, the real victories come in the smallest moments: a child pointing to a picture to communicate, another who finally sits through a full session, or a parent whispering “thank you” with tears in their eyes. These everyday breakthroughs are everything.

Her personal experience as a parent gives Sandhya a unique lens. She understands the fears, hopes, and quiet triumphs families carry. That’s why parental involvement is not optional at the centre — it’s essential. Families regularly participate in progress meetings, classroom observations, and hands-on training. Home goals — practical and doable — are shared, and customised visual aids help ensure continuity beyond school hours. Emotional support is offered just as readily as academic strategies.

Still, the challenges are real. There is a pressing shortage of professionals trained in autism-specific interventions, especially for students with high support needs. Assistive communication tools are expensive and often out of reach. Space is limited, even as demand grows. Sandhya dreams of expanding — with dedicated sensory rooms, inclusive playgrounds, and classrooms designed for neurodivergent learners. “These help children feel safe, calm, and ready to learn,” she says.

Her vision for the future is clear: inclusion that goes beyond tokenism. She dreams of classrooms where neurodivergent children aren’t merely accommodated, but genuinely valued — where belonging is a given, not a gift. To get there, she believes we must build on three pillars: Mindset (a shift from awareness to true acceptance), Capacity (training educators, therapists, and families), and Belonging (where every child is emotionally safe and socially included).

As she looks ahead, Sandhya hopes to increase enrolment, offer structured training for parents and teachers, partner with inclusive schools for smooth transitions, and support students well into adulthood — through vocational training, community participation, and self-advocacy.

Her journey is a reminder that special education isn’t just about what children need — it’s about what they deserve.

Because, as Sandhya says,

“In every smile, there’s a victory. And every child deserves to smile.”

Read the full story in our issue of Teacher Warriors 2025 here.

Education

Indian Army to Sponsor Education of 10-Year-Old Who Aided Troops During Operation Sindoor

In a heartwarming gesture of gratitude, the Indian Army has pledged to fully sponsor the education of 10-year-old Shvan Singh, a young boy from Punjab’s Ferozepur district who supported troops with food and water during the intense gunfire of Operation Sindoor.

During the cross-border conflict in early May, Shvan—then mistakenly reported as ‘Svarn’ Singh—fearlessly stepped up to help soldiers stationed near Tara Wali village, just 2 km from the international border. With lassi, tea, milk, and ice in hand, the Class 4 student made repeated trips, delivering supplies to the troops amid ongoing shelling and sniper fire.

Moved by his courage, the Golden Arrow Division of the Indian Army has now taken full responsibility for Shvan’s educational expenses. In a formal ceremony held at Ferozepur Cantonment, Lt Gen Manoj Kumar Katiyar, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief of the Western Command, felicitated the boy and applauded his spirit of service.

“I want to become a ‘fauji’ when I grow up. I want to serve the country,” Shvan had told media in May. His father added, “We are proud of him. Even the soldiers loved him.”

Shvan’s actions during Operation Sindoor—India’s strategic missile strike on nine terror camps across the border in retaliation to the Pahalgam attack—have now turned him into a symbol of quiet heroism and youthful patriotism.

In a world where headlines are often dominated by despair, Shvan’s story reminds us that bravery has no age—and that the seeds of service can bloom early.

Education

Lighting the Way, One Beam at a Time – Monika Banga

In the stillness of the COVID-19 lockdown—when the world hit pause and uncertainty gripped communities—Monika Banga quietly sparked something radical. Not radical in funding or scale, but in spirit. Born out of a moment of global stillness, The LightBeam Project wasn’t launched with loud declarations or big grants. It began as something far more intimate: a bridge between continents, classrooms, and possibilities.

But Ms. Monika’s journey didn’t start there. It began over a decade earlier, in under-resourced classrooms where she worked with children who had never known structured learning, or imagined speaking with someone from another country. With over 12 years of experience, she didn’t just teach—she listened. And what she heard, again and again, was a hunger not for food, but for discovery, belonging, and expression.

When the Granny Cloud initiative—a volunteer-driven project that connected retired educators with children—came to a close, Monika felt the silence it left behind. Along with her friend and fellow educationist Lesley Keast from Spain, she wondered: What if that spark of connection could be reignited? That one idea gave birth to The LightBeam Project. It began modestly: a handful of volunteers, one school, a few curious children, and shaky internet. But it carried a powerful belief: every child has the right to dream, and someone, somewhere, will listen.

Unlike traditional education interventions, LightBeam didn’t come with a manual. It came with open-ended conversations. Sessions inspired by SOLE (Self-Organised Learning Environments) nudged children toward self-discovery. Initially, the children were hesitant.

“They were used to answers, not questions,” Monika recalls.

But soon, wonder took over. They began asking: Why do we age? What if all insects disappeared? These weren’t sessions—they became rituals of curiosity.

As their questions deepened, so did their digital skills. Devices once used for distraction turned into tools of creation. Children began making digital presentations, recording videos, and sharing local traditions with volunteers across the globe. One girl proudly made a Canva slideshow introducing her Beamer to her village’s customs. These weren’t just projects. They were windows into identity.

Lesley Keast, one of LightBeam’s earliest volunteers, reflects on the transformation she’s seen. “The children now have SOLE sessions in their learning DNA. They own the enquiry. They direct the wonder.” For her, the project isn’t just about teaching—it’s about being part of a global community stitched together by purpose. “Our WhatsApp and Facebook groups are more than admin tools. They’re our digital campfires,” she smiles.

Sometimes, it’s the smallest moments that leave the biggest marks. In one session disrupted by technical issues, Lesley recorded a video and sent it to the students with a few questions. They responded with videos of their own. One came from Ruby, a student who had never spoken during any session. With support from her peers, she sent a video back—radiant with confidence. “That’s when the ice cracked,” Lesley said.

In another session, students chose their own topics and returned with insights on dark matter and Freud. “We thought those were far beyond them,” Lesley said. “But with no ceilings, they soared.”

The LightBeam Project has no classrooms. And that’s its strength. By embedding itself into existing schools—like DIKSHA in Gurgaon—it stays grounded. DIKSHA, Monika shares, has been a pillar, ensuring support, space, and safety for these sessions. The absence of fixed walls creates a flexibility rare in educational systems. Sessions can happen anywhere children and curiosity meet.

The project’s growth depends on sustained partnerships—with schools, funders, and storytellers. “Support in storytelling,” Monika says, “goes a long way. Stories beam us into places we’ve never been.”

For teachers who feel trapped by rigid systems, Monika’s advice is gentle: Start small. Ask students what they’re curious about. Let them explore. Joy isn’t the enemy of rigour—it fuels it. And agency doesn’t create chaos. It creates connection.

Through The LightBeam Project, Monika Banga has redefined what education looks like in a post-pandemic world. Not transmission, but transformation. Not instruction, but invitation. Each call is a candle lit. Each question, a door opened. Each child, a beam of light—brighter than the last.

Education

Dancing Beyond Boundaries – The Story of Krithiga Ravichandran

In the heart of Puducherry, where colonial buildings wear salt stains and stories, lives a woman quietly orchestrating a revolution — barefoot, graceful, and defiant. Krithiga Ravichandran, a Bharatanatyam dancer and Assistant Professor of Computer Science, moves between two seemingly different worlds. But look closer, and both are bound by the same rhythm — teaching, nurturing, and transforming.

Born into a family where the arts were heritage, not hobby, Krithiga was raised by the sounds of mridangam, violin, and Carnatic ragas. Her earliest memories? Her grandmother reciting jathis while tapping on a steel plate. “That was my first dance class,” she recalls. “No stage. Just the veranda and a heart full of movement.” By five, she was training formally in Bharatanatyam. And yet, even then, she saw how exclusionary the classical arts could be. The costs — of costumes, jewellery, music recordings — kept so many young girls out.

In 2014, on her birthday, Krithiga founded the Veer Foundation of Arts and Culture Trust, inspired by her father’s values of service. With it, she began offering free Bharatanatyam classes to underprivileged girls. These weren’t just lessons in movement, but in identity. Under temple porticos, community halls, and now small studios, these girls train rigorously — not to perform for others, but to discover themselves.

When she’s not dancing, Krithiga teaches Computer Science at Indira Gandhi Arts and Science College.

“Whether I’m breaking down a loop or a mudra, it’s the same joy — watching a student’s eyes light up.”

Her days begin with code and end in abhinaya. Yet, this rhythm energizes her — it’s how she lives her purpose.

Over the years, shy girls who once hesitated to speak now take the stage with confidence. Dance has offered them more than grace — it has given them resilience. “They come unsure,” Krithiga says. “But they bloom. They plan rehearsals, mentor juniors, manage logistics. They lead.” What begins as dance becomes training in leadership, storytelling, budgeting, and cultural memory.

Dancers in the Making, Leaders in the Wings

In a pioneering move, Krithiga introduced Bharatanatyam as a therapeutic tool inside Puducherry’s Central Prison. “It was experimental,” she admits. “But we saw remarkable change — calmness, awareness, even hope.”

Some questioned her decision. “Why offer sacred art to prisoners?” But she insists: “Who better to understand longing and repentance?” To Krithiga, art must include. Art must heal.

Creating safe, inclusive spaces for marginalised girls remains central to her vision. “They don’t just need a guru. They need a safe adult.” She counsels, supports, and makes sure no girl feels alone. From arranging transport to lending jewellery, she builds a circle of trust around them. Much of it runs on her own earnings. “If you believe in something, you fund it — with time, energy, and soul.”

Though she receives small donations — old costumes, music books — she’s kept the work intimate and rooted. “Every piece of jewellery on stage has a story,” she says. “Someone’s daughter outgrew it, someone remembered their Arangetram. It’s a circle of generosity.”

“Dance Doesn’t Ask Who You Are. It Asks, How Do You Feel?”

Krithiga’s vision is to build a holistic centre for classical arts — with a stage, library, wellness wing, and space for reflection. “I don’t want to just train dancers. I want to raise artists — those who know the pulse of the past and can choreograph the future.”

To her, Bharatanatyam isn’t ornamental. It’s essential. A language of liberation — especially for those the world forgets to watch.

Education

The Man Who Called His Students Gods: Dwijendranath Ghosh

Dwijendranath Ghosh calls himself ordinary.

But how many “ordinary” people spend their retirement building a school from scratch — with no funding, no government salary, and no promise of support? How many choose to teach every day, without compensation, well into their 70s? And how many refer to their students — many from the most marginalised sections of rural Bengal — as gods?

At 78, Ghosh is the heart and soul of Basantapur Junior High School in West Bengal’s Hooghly district. He opens the gate each morning. He teaches children for free. He never left his village — but his impact now reaches far beyond it.

From Barefoot Dreams to Blackboards

Ghosh’s journey is rooted in personal struggle. Growing up in deep poverty, he had no books, no uniforms, and no certainty. His childhood was spent walking barefoot to school, borrowing textbooks, and studying by the glow of kerosene lamps. And yet, he rose. A master’s degree from Burdwan University followed in 1973.

“The pain of those days still haunts me,” he says. “But it also shaped me.”

That pain turned into purpose. Soon after graduating, he and a few friends began running an informal high school in their village—unrecognised, unpaid, but unstoppable. For nine years, they taught with nothing but commitment. When the government finally recognised the school in 1982, Ghosh had already left to take a government job elsewhere, forced by financial needs.

The Second School

He retired in 2008. But instead of resting, he returned to his village and found that little had changed. Girls were still dropping out after primary school. Child marriage was common. A generation was fading into invisibility. So he began again. With no funding, no building, and no staff, he worked for five years to create Basantapur Junior High School.

In 2014, the school was officially recognised. But the journey was never about the paperwork — it was about presence. Every morning, Ghosh arrives before the first bell. He teaches, supports, and uplifts — without compensation. Because for him, teaching is service.

A Volunteer Army — Running on Faith

He’s not alone. A team of young, educated, but unemployed volunteer teachers stands beside him. They could have chosen easier paths, but chose this one out of belief, not benefit. They are unpaid. At times, local donors offer small stipends, but it’s inconsistent. Most are struggling, yet they return every day. “They have given the most valuable years of their lives,” Ghosh says.

The school receives only ₹25,000 a year as a government grant. For three years, even that was inaccessible. What kept it alive? Former students, now grown, are donating what they can. The community is pitching in. Alumni returning to teach. When a government teacher recently disrespected the volunteers, the team almost walked out. But students and parents wouldn’t let them. Ghosh stepped in to calm tensions.

“We can’t let one bad moment undo decades of good,” he told them.

A Temple Against Child Marriage

One of the school’s biggest challenges is child marriage. In villages like Basantapur, girls are often married by 14—seen as burdens, not futures. By offering local access to education, the school has become a shield. Many girls have completed higher education here. But the battle continues. “This trend,” Ghosh says, “is like an infection. It keeps coming back.”

At Basantapur Junior High School, learning is about more than grades. Students perform in cultural shows, play football and cricket, and take part in morning assemblies. They learn to speak, to lead, to dream. There’s no structured life skills module—because the school itself is the life lesson. Students know they are seen, heard, and cared for. Teachers know their work matters. And visitors walk away knowing this is not just a school—it’s a movement.

His empathy, his daily discipline, and his belief in every child form the blueprint that his students follow. And his impact lives in their dreams.

The Final Lesson

What does his family think?

“They worry about my health,” he laughs. “Not about the money.”

His pension is enough for his needs. What he seeks is not comfort — but recognition for his team. “These teachers have earned the right to be made permanent. A hundred times over,” he says.

When asked what keeps him going, he simply says:

“So long as I am in the school, I am alive.”

In an education system obsessed with metrics, Ghosh offers something rare: meaning.

He didn’t build a career.

He built a sanctuary.

He didn’t earn a salary.

He earned generations of gratitude.

And in every child who enters Basantapur Junior High, the final lesson is quietly imprinted:

Service is not sacrifice. It’s grace.

-

Inspiration3 months ago

Inspiration3 months agoUmeed: A Ray of Hope for Better Tomorrow

-

Knowledge1 month ago

Knowledge1 month agoBuilding a Healthier India: Why School Health Programs Are Essential

-

Inspiration1 month ago

Inspiration1 month agoBefore the Nobel, There Was a Teacher

-

Education1 month ago

Education1 month agoWhat the Indian Army Teaches Our Children Beyond Textbooks

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoInclusive Education Summit 2026: Designing the Future of “Learner-Centric” Education

-

Education3 weeks ago

Education3 weeks agoBeyond the First Bell: 5 Key Takeaways for School Leaders from Economic Survey 2025–26

-

Education3 weeks ago

Education3 weeks agoSupreme Court’s Landmark Judgment for Schools: Menstrual Health is a Fundamental Right

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoJudicial Guardrails: How the J&K High Court’s Fee Regulation Verdict Redraws the Rules for Private Schools